By: 4R Plus

September 2018

Soil erosion in Iowa is occurring about 10 times faster than soil is being renewed, says Rick Cruse, Ph.D., agronomy professor at Iowa State University and director of the Iowa Water Center. But he believes that statistic would improve if farmers think about what the soil on their farms will look like in 20, 50 or even 100 years.

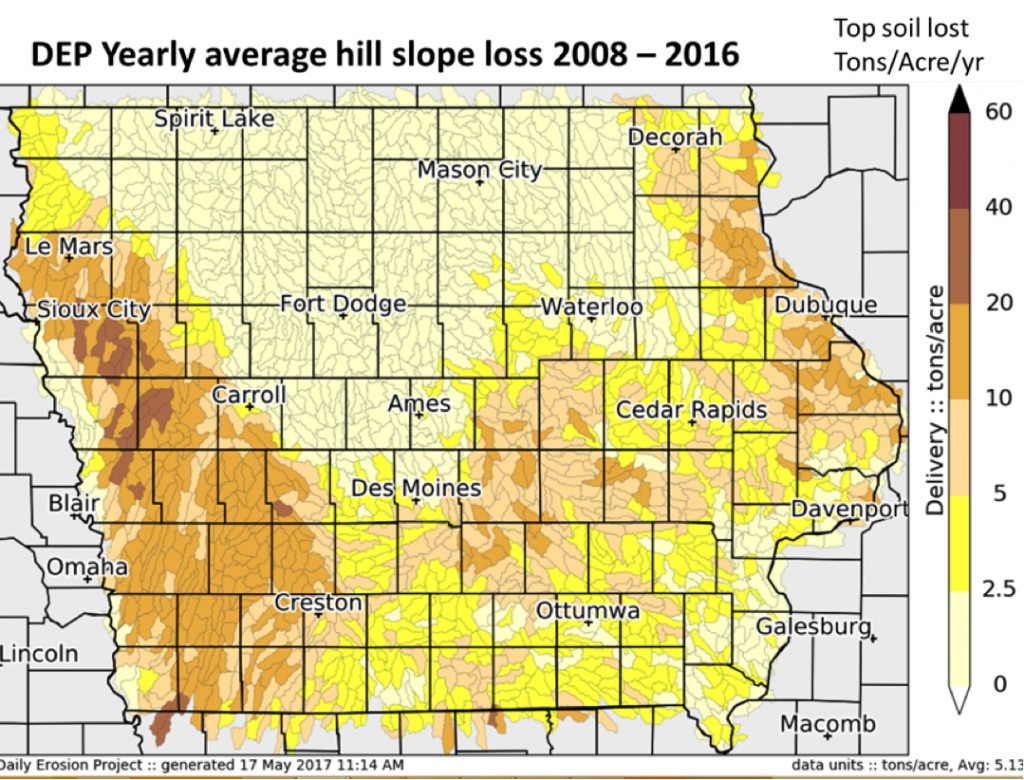

On average, Iowa is losing about 5 tons of soil per acre per year. The deepest soils in Iowa are on the Loess Hills of western Iowa, but that’s also home of the greatest soil loss. “The hills are steep, the soil material is highly erodible and it doesn’t have much resistance to movement,” said Cruse.

Sioux County, Iowa, farmer Theo Bartman implements conservation practices to improve soil health and stop erosion on his northwest Iowa farm. “I hate seeing soil loss on the hills of western Iowa. I have implemented a no-till system to minimize disturbance to the soil and have added cover crops to improve organic matter and help with erosion,” he said. “To have a long future in farming ahead of me, I knew I had to do some things differently.”

Cruse says weather patterns are changing and with it brings increased instability in precipitation. “We’ll see stronger precipitation events spread further apart,” he said. “We don’t know how improved crop hybrids and genetics will respond, but there is no question crops need water and soil with good water-holding capacity. For every inch of soil gone, also gone is roughly half an inch of pore space to store water.”

Cruse recognizes today’s crop yields are impressive. “Crop yield technology is a great tool, but it’s not a solution to our soil problems,” he said. “We see yield reductions in areas where soil loss has occurred. Even though the yield curve is rising, one concern is that some of our soil conditions are declining.”

Cruse co-leads the Daily Erosion Project, which estimates soil erosion every day using remote-sensed information to measure precipitation and satellites that gather information on the crop systems being used. He uses data from the project to start conversations with farmers about keeping soil in place.

“A group in southwest Iowa was surprised by the state’s soil loss statistics I was sharing with them because they utilize no-till, have terraces and use cover crops. But I asked them if everyone uses those practices,” said Cruse. “That got them thinking about the changes they have made in their conservation practices to preserve and improve the soil that they are farming. They understood the importance of everyone doing their part.”

Bartman encourages farmers to do their own trials with cover crops and no-till to improve soil health and stop erosion. “The first year we planted half of a sloped field to cover crops and the other half of the field we did not plant cover crops,” he explains. “The half that had cover crops was also no-tilled and the half without cover crops was tilled. We saw a tremendous reduction in erosion in the half of the field with cover crops and no-till and became convinced we found a better way.”

Cruse says when you drive through the countryside in the spring before there’s anything growing, look for the light areas in the fields. He says in many fields, those are areas that have lost topsoil and are generally less profitable. He encourages farmers to take advantage of their yield and cost-of-production data to recognize areas in fields that are not profitable and implement a soil health practice to rebuild soil health.

“Agriculture manages biology. It’s not a one-size-fits-all system,” said Cruse. “Use your data to determine where your soil health challenges are occurring and investigate solutions that will keep soil in place, productive and profitable for generations to come.”