By: 4R Plus

April 2020

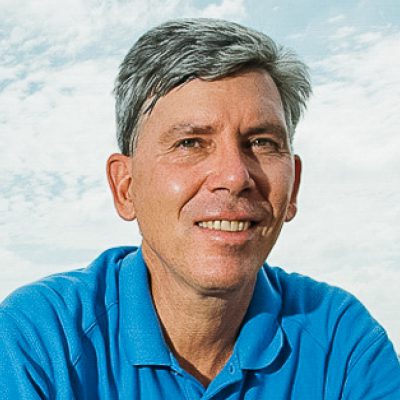

Mahaska County farmer Mark Jackson defines sustainability as having the economics of farming in balance with his community and the environment. He uses 4R Plus practices to achieve that goal.

Jackson switched to no-till 25 years ago on his fairly flat to rolling land to eliminate soil erosion. He saw improvements in the soil’s ability to hold water through the years and in 2012, began experimenting with cover crops to rebuild organic matter and sequester nutrients.

Since adding cover crops to all his acres, the soil has greater water-holding capacity and he’s starting to see some weed suppression – all while reaching his corn and soybean production goals.

“We harvested some record soybean yields last year,” said Jackson. “I can’t help but think some of that was attributed to the cover crop and the improvements in the soil structure given the fact we planted in the middle of June amid tremendously wet soils. We are consistently at or above county yield averages.”

He’s the first to admit changing his mindset about tillage and cover crops was a process. “Many farmers with full tillage systems see outstanding yields, but the organic matter is decreasing,” Jackson said. “It was strange no-tilling soybeans into cornstalks the first time, but now we’re comfortable planting soybeans into standing rye.

“After you make the change in your system, your opinion about a practice changes as you see positive results,” he added.

Jackson recently purchased a piece of land that was tilled for years. “Comparing the organic matter in the fence line to the tilled areas of the field shows a large disparity,” he said. “It takes about 10 years to gain 1% of organic matter; we can’t afford to waste any more time.”

As he prepares for planting, Jackson is encouraged by cover crop growth. He has experimented with different methods of termination and came to the conclusion on his farm that there is no yield drag planting into standing rye and it saves a pass across the field. “I’m comfortable planting soybeans into shoulder-high rye as long as it’s not headed out,” he said.

For corn, Jackson terminates the rye if it’s more than a foot tall at planting time. “Planting a legume into rye is different than planting corn into rye,” he added. “There’s more competition between corn and the rye.”

After harvest, Jackson has learned not to let the weather discourage him from getting cover crops seeded. “Last fall we drilled several days in the semi-frozen ground. In rare instances the seed will germinate at the wrong time, but I encourage farmers to just keep planting,” he said. “Every year is different. Over time the learning curve gets easier.”

As he reflects on the changes he’s made to preserve the soil, Jackson, who farms with his son, knows he’s doing the right thing for the land that’s been passed down through multiple generations. “I have not made a single mistake in this process, but there’s a long list of things I wouldn’t do again,” he quipped.

“At the end of the day, it’s the process of continual improvement that keeps me fired up,” he said. “It’s rewarding to pass those lessons to my son as well as gain from his wisdom and perspective.”

During a 2014 TED Talk, Jackson explains his passion for farming and efforts to protect the soil and environment.